Written by Robert Frazer on 29 Sep 2014

Distributor Viz Media • Author/Artist Motoro Mase • Price £8.99

Reviews are normally about testing out the temperature of what's hot, but this particular review also gives us an opportunity to see whether something from the past has stayed cool. The UK Anime Network reviewed the first volume of Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit way back in 2009, and ever since then this series has quietly puttered through its course of biennial releases with little comment or fanfare until today, as the series concludes with the final Volume 10. It must be said that Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit has not been a series that has been sparking with anticipation on the lips of every manga reader who were rocking on tenterhooks with bated breath for new chapters - but we mustn't underestimate it, for it would not have been able to complete five years of releases if it didn't enjoy the support of a loyal and dedicated readership.

The original Japanese edition of this series had enough momentum to make the leap from the cancellation of its original magazine, Weekly Young Sunday, and continue in Big Comic Spirits up to the end of its seven-year run from 2005 to 2012. It's been published in multiple countries across Europe and Asia and it has also had a 2008 live-action movie released in the UK by MVM last year as Death Notice: Ikigami, which like Sin City anthologised some of the manga's individual stories, although there was no effort to cross-promote the film and the manga over here (there isn't so much a "now a major motion picture!" sticker on the cover of this volume) which seems to have been a missed opportunity. With a faithful fanbase that's supported subsequent volumes of Viz's manga over several years though, the extra expense would seem unnecessary. Now that the series is drawing to a close, will the readers have a satisfactory pay-off and a fulfilling denouement to the story that they have invested time and money into realising, or has their patience run up against its own ultimate limit?

It has long been the government's concern that the social fabricis unravelling. Everywhere you look, selfishness and insularity prevail over community and commonality; society has been corrupted by the sheer toxicity of modern life. What antidote can counteract such a potent public poison? To restore civility to civilisation, the government has signed into law the National Welfare Act, and created the National Ministry of Welfare and Health to administer it.

Every year, young children go to in their schools' sports halls to receive their mandatory vaccinations. The long queues and snivelling of kids scared of needles is ordinary, routine and boring... but in amongst the sterile trays of hypodermics is something exceptional. One in a thousand vaccination courses is also filled with a minute nano-capsule. This capsule migrates to the brain where, at some point between the host's age of 18 and 24, it will burst and kill him instantly with a catastrophic aneurism. Administered blind to a randomly-selected patient, the carrier of the capsule lives his life in ignorance, completely unaware that his days are quite literally numbered, until one day he gets a knock at the door from an anonymous bureaucrat who hands him a sheaf of documents. This paperwork informs him that over a decade ago he was volunteered for the honourable service of giving up his life for the good of society and that within 24 hours, he will be dead. These are his Death Papers - his Ikigami.

Truly, there's nothing sure in life but death and taxes - even when the government has announced that it's killing you it still obliges some of your time, as there's forms to fill out, release dockets to sign, receipts to exchange. Then, with a polite goodbye, the factotum closes the door behind him and you are left alone. The theory behind the National Welfare Act goes that the knowledge that anyone could receive an Ikigami will encourage people to be more reflective about the fragility and value of life, and so be motivated to use their time more productively and fruitfully to take fuller advantage of a potentially limited span, so increasing social good and both public and personal happiness. Is it much consolation to the man whose passport photo is on the innocuous little card paperclipped to the front of the Notes of Explanation for Next of Kin, though? What good can you do - for society or yourself - when you only have one day left to live?

It's easy to point out the many practical problems with the Ikigami system. It must occasion not a little embarrassment to the State if the recipient of the Ikigami was out late drinking with friends and didn't find the papers in his mailbox until there's just ten minutes to go before he pops, or was away on vacation when the delivery came round - it doesn't dignify the inspiration of Government or the good of society when a guy in his Speedos is keeling over on a foreign beach with ice cream dribbling down his sunburn - but if you can bear some impracticalities on your suspension of disbelief then the high-concept of "what would you do if you had one day left to live?" is very engaging. It can be an arresting and compelling one that any reader can be thoughtful about and reflect on precisely because of the ordinary circumstances and diverse professions of those who receive the Death Papers. However Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit's main problem throughout its entire run has always been that it cannot believe its own central conceit - after setting up the situation, it spends far too many pages tearing down what it's only just built.

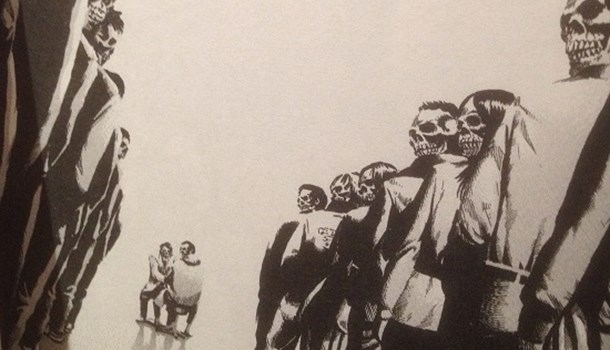

You can naturally expect there to be a great deal of opposition to a regime of state-sponsored murder, where dissenters are dragged from their homes by masked riot police and "enrolled into the curriculum of correct thought", and true enough our point-of-view character the Ministry of Welfare and Health civil servant Fujimoto has sickened of National Welfare over the course of the series. However, these feelings of rebellion are common to any one of a thousand sci-fi dystopias and while there were intermittent flashes of drama over the course of the series - in a previous volume Fujimoto reported several "social miscreants" who suggested he join their resistance because of his yellow-bellied terror of being caught himself, which was a very honest depiction - by and large they are drearily rote and predictable and entirely uninspired. More than its weary turning-over of tepid reheated revolutionary politics, Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit was always far more interesting when it just accepted its own premise as a plain statement of the situation and told individual stories of people confronted with the fatal boundary and trying to find some solace and worth in their situation, with a constellation of different reactions to that one hanging question of "what to do when you have one day left"? Even if it was frequently expressed in heavy-handed Aesops and didactic morals, these were nonetheless characterful, emotional human tales that explored the reaches of our hopes and fears in a constellation of different reactions to that one final question. In Volume 10, though, as the stresses behind National Welfare reach breaking point in the social upheaval that it was supposed to prevent, the better half of Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit falls by the wayside as the manga becomes preoccupied, again, with the ponderous plod of Plot.

That was a pothole in the road that was seen well ahead, but despite that advance warning Volume 10 of Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit still stumbles into it with a very sudden new problem that is quite abruptly foisted on us in this last volume. While it may have been predictable, like the rudderless mediocrity of the regime in Terry Gillam's Brazil the oppressiveness of the scenario in Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit was chillingly effective because of how suburban it was - Fujimoto's supervisor is not a clipped, icy, black-suited G-Man but a balding civil servant with a roll of middle-aged spread. The "National Welfare Act" itself is amorphous and irrepressible in its ungraspable, pervasive, thoughtless blandness. There was a powerful, threatening sense of "it could happen here!" which spoke meaningfully to Japan's own social problems with the conformist self-subjugation as protestors are pilloried as "social miscreants". However, that's all thrown away in Volume 10 as we really quite suddenly find out that we're not in Japan after all... "this country" is a not-Japan which has Japanese ethnicities, Japanese language, Japanese currency, Japanese architecture and government - but is not Japan, no sir, and neither is "our ally" in any way America. I suppose it's not as bad as Jormungand which made so little effort to integrate its diplomatic skulduggery into the real world it literally just called places "Country A" and "Country B", but it's just so unnecessarily convoluted and actually robs the story of a lot of impact. You could argue that the warnings both about self-destructive self-restrictions and the point that emerges in Japan's complicity in U.S. Pacific hegemony are still there to be read, but the redundant degree of separation, like a layer of rubber protecting the skin from the air, numbs and slows the reader's reaction. The urgency, the immediacy is lost - rather than looking about himself to see how Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit is reflected in his own life, the reader is invited to scoff a little and reassure himself that it could never happen here, or hasn't happened yet and there's no need to worry just right now, and so readers sleepwalk past the warnings.

It's such a shame, because for all of my complaints about the conventionality of Fujimoto's struggles, there is one fiery flash of bleak black brutal brilliance in the penultimate chapter, where the true final purpose of the National Welfare Act and the Ikigami is revealed. It's a cruelly, calculatingly cynical strategy that lays bare the futility of the system in a dramatic, forceful ripping aside of the curtain, throwing light onto the shape of something that was genuinely in the dark and undefined before then. It's a real, honest-to-goodness surprise twist, the sort you wouldn't think that manga with its endemic over-reliance on tropes was even capable of doing.

And then the manga goes and spoils it.

Had Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit ended on this point it would have been genius - a compellingly awful catharthic tragedy, a strident and thundering topical polemic and a dystopian triumph. Alas, though, the formulaic three-act structure for each story that the manga has stuck to rigidly for ten volumes will not bend even for the end and the demand to fill out the empty Part Three of Episode Twenty means that the rebel yell coughs and wheezes to bum note - the manga cops out with a lame, syrupy happy ending where the characters are quite literally sailing off into the sunset. At least, for all the ten minutes it would have taken for the police to rustle up a helicopter and winch them off the ship again, but that doesn't seem to trouble our heroes too much. I suppose in some way it's moving - I feel as hollow as an Ikigami recipient must do as their stomachs are pitted by the leaden weight of finality. The manga commits hara-kiri right before your very eyes. It is truly Japanese.

All that's left to do now is exaime the corpse. The outsized format of the Viz Signature releases does serve Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit well because one strength it does have going for it is good art. While cityscapes are incredibly lazy - frequently just photographs with a screentone filter thrown on top - indoor backgrounds are fine and human characters enjoy superb detail and facial definition that is brought out with impact by the larger pages. This is especially important because Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit is a very talky manga - one whole chapter in this volume is literally nothing other than two people talking in a hallway - but close-ups are not just blank big-eye blandness and shifting camera angles keep the dialogue rallies dynamic. I do like the consistent cover design maintained across the length of the series as well, it has strong branding.

One weird feature on that cover though is the "Explicit Content" warning on the corner. This is completely nonsensical - seriously, there's absolutely nothing here to warrant it: utterly zero sex (even implicitly), modest and almost bloodless violence, and the most dreadful, scathing, vilest insult someone can spit is "you rotten bureaucrat". No, really! It's been the same throughout the series' entire run (even when the manga attempted a rape scene in a previous volume both characters were fully clothed) and I've long assumed that it's just there only so that the Viz Signature label can polish it's "mature" credentials,

Sadly, after five years, I depart from Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit with... disappointment. With its preoccupation with plot over personal experience it has missed its own point and ignored its own strength and the genuine power of its final reveal was too weighed down with the ballast of the abrupt change in setting and needless padding in order to take flight. Well-intentioned, confidently drawn but wildly off-the-mark, Ikigami: The Ultimate Limit has run out of time and is now dead.

Robert's life is one regularly on the move, but be it up hill or down dale giant robots and cute girls are a constant comfort - limited only by how many manga you can stuff into a bursting rucksack.

posted by Eoghan O'Connell on 25 Nov 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 06 Nov 2025

posted by Eoghan O'Connell on 05 Nov 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 21 Oct 2025

posted by Eoghan O'Connell on 18 Oct 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 26 Sep 2025

posted by Eoghan O'Connell on 23 Sep 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 16 Sep 2025