Written by Richard Durrance on 23 Sep 2024

Distributor Eureka, Masters of Cinema • Certificate 15 • Price £17.99

We seem to be in a golden period for Kinji Fukasaku releases. The Threat coming out from Arrow, alongside their prior discs; Radiance have given us Yakuza Graveyard and Sympathy for the Underdog. Now Eureka have released his 1964 Wolves, Pigs and Men, having previously given us Samurai Reincarnation, The Fall of Ako Castle, and more. Wolves, Pigs and Men is also an unusual release in being quite an early film in his oeuvre, as is The Theat.

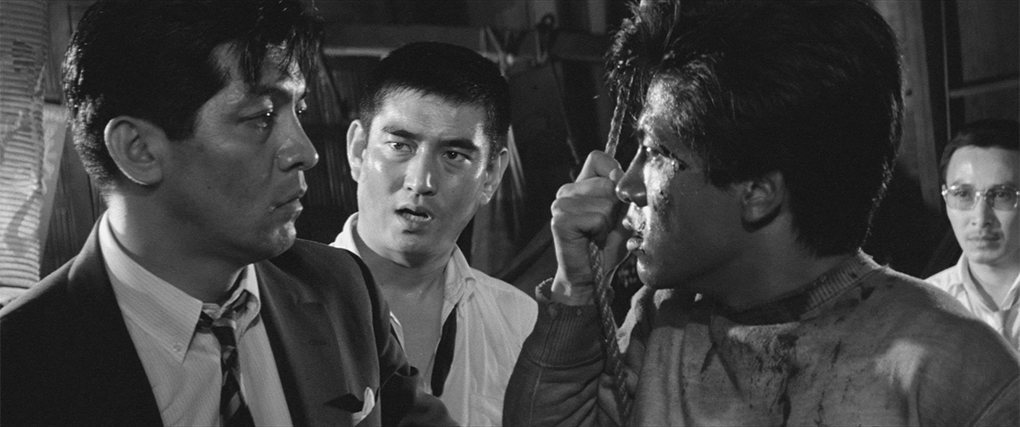

Living in the slums, Jiro (Ken Takakura) follows in the footsteps of his elder-brother, Kuroki (Rentaro Mikuni) to become a yakuza, both leaving their youngest brother, Sabu (Kinya Kitaoji) to look after their ailing mother. Jiro being on the opposing side to Kuroki is railroaded into prison then released, and goes about scheming to rip off the yakuza clan that got him jailed.

Many of Fukasaku’s earlier works are often described in the context to how they relate to his Battles without Honour and Humanity films. Much of this seems to be because many of his earlier films so far released have never been quite so nihilistically bleak as the Battles films (or his later Graveyard of Honour), though Wolves, Pigs and Men may be an exception. At least it is an exception in those I’ve seen to date.

It’s a fascinating film, because it seems to have many influences, and potentially have numerous moments required by the studio, which Fukasaku manages not to undermine but instead absorb into the film’s tone. Even the film’s title seems to reference Shohei Imamura’s 1961 Pigs and Battleships (which I admit I’ve not seen in a long time). There are moments in the film that feel reminiscent of a Nikkatsu youth film, with Sabu and his friend’s dancing to American music. The opening of the film is intriguingly poised, as its montages seem influenced by American movies: with the neon nightlife overlaying Takakura’s Jiro, yet it is also very Fukasaku, with backstory told in voiceover and accompanied by still images, to efficiently and effectively deliver backstory but always with style. Even in this early work aspects of his signature yakuza style seem already fully formed.

Then we get into genre.

In part this is the failed heist film. It’s a sibling drama. It's a youth film. It's a socially conscious drama. Yet it is all these things and more and what fascinates is how so early in his career Fukasaku seems to be so totally in control of what he’s doing. The youth movie scenes feel like nothing Nikkatsu ever put out, and there’s a darkness there, a grungy disaffection that is disturbing. I don’t know if Fukasaku was required to have these scenes, but like Seijun Suzuki often does in his potboiler work, Fukasaku does with them what he can. Or rather, to enforce his own view on them. Arguably it doesn’t matter as these aspects integrate into the narrative, because these scenes are not just about appealing to a youth audience but illustrate how Sabu and his friends are shown to be a close unit, and this matters because the heist when it occurs doesn’t so much go wrong as Sabu assumes Jiro and his partner are going to double cross him and his mates; at the same time Jiro and his partner are trying to double-cross each other. Sabu, hiding the money, takes a beating and so do his friends, to hide it from Jiro and his partner.

And these scenes are restrained to an extent but are also brutal in a almost Scorsese way of examining the violent mind. What Fukasaku presents to us is unflinching but the violence is of course there to underscore the more social aspects of the film. The brothers and their mother live in a slum that is referred to as a pigsty, and as often is the case, the one way out is violence, to feed off the misery of others. So for as much as this is a failed heist movie, it is really digging away at the brutal reality of life after the war. Even the mother’s funeral is casually shocking.

Tonally then it feels similar to his seventies work, and I was repeatedly surprised by how much Fukasaku gets away with; it is an excoriating film and one that could be deeply unsympathetic. Having Ken Takakura play Jiro certainly helps, as his character could be visualised as an almost emotionlessly evil man, but Takakura imbues him with just enough humanity to keep him semi-relatable. Almost no character you could argue is spared, because even Sabu and his friends allow each other to go through terrible harm for the sake of money. Perhaps the closest to dignity is the older brother Kuroki, who would have had Jiro leave town - but here blood is definitely not thicker than water.

Much of the film takes place in one location but you never feel it, if anything the closeness of the location feels palpably oppressive, especially for the characters. The dingy shack where all three brothers, the conspirators, end up feels almost symbolic in how they’ve come full circle and how the world will always suck you back to your roots and perhaps provide some rough justice.

Of his 1960’s work, Wolves, Pigs and Men to me feels the most Fukasaku, the most brutal, curiously perhaps also the most human. It delves into the lingering social impact of the war almost without you noticing and in doing so provides us with a remarkably powerful thriller/drama and one that stands tall alongside his later work.

Long-time anime dilettante and general lover of cinema. Obsessive re-watcher of 'stuff'. Has issues with dubs. Will go off on tangents about other things that no one else cares about but is sadly passionate about. (Also, parentheses come as standard.) Looks curiously like Jo Shishido, hamster cheeks and all.

posted by Richard Durrance on 12 Dec 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 09 Dec 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 28 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 25 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 18 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 14 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 11 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 07 Nov 2025