Written by Richard Durrance on 09 Oct 2023

Warning: some spoilers will be in evidence. I’ve tired to keep it to a minimum but I’m only human.

The Boy and The Heron, or How Do You Live?, may be one of the most hyped animated films of my - or any - lifetime. Hardly a surprise considering Hayao Miyazaki is perhaps the one true director of animated films to really break boundaries and that this was meant to be his final film. The hype is understandable.

I managed to snag a London Film Festival (LFF) ticket, even though it meant a seat right at the back by the sound guys. This was not at any cinema either, taking place at the Royal Festival Hall to a packed house, playing for the first time to a paying audience in the UK.

Watching such a film it would be wrong not to consider expectation: the audience will be expecting a masterpiece, and with that is the other risk, being overly critical because the audience will be wanting a level of quality few could hope to match, or consistently produce.

As one of the LFF directors walked onstage to introduce the film to a packed house, the goodwill was palpable. Sure, there would be some folk in the audience with complementary tickets there for whatever freebies they could grab, but the overwhelming sense of joy of the film about to unfold, especially as it was then announced the film almost never made it to the LFF, filled the sizeable auditorium.

Then the lights dimmed.

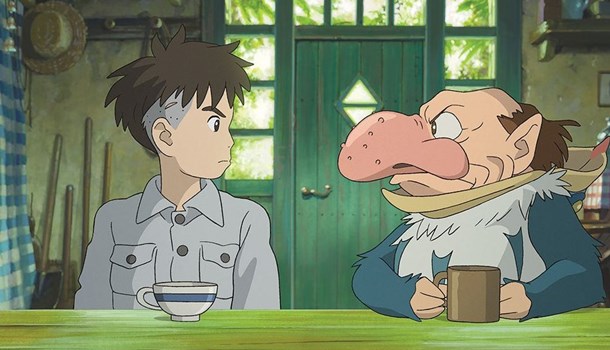

Tragedy hits young Mahito (Soma Santoki), as his mother dies in a fire. He is sent into the country with his father, Shoichi (Takuya Kimura), who runs factory churning out aircraft parts for the war effort. Here, Mahito is met by Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), his new mother, and the cadre of elderly women who run the household. A Grey Heron (Masaki Suda) appears, appearing at first to welcome him, then beckoning him towards a ruined tower on the grounds that has an unusual history. Suddenly more menacing, the Grey Heron leads Mahito into a strange fantasy land.

From the very first moment, both visuals and design are pure Miyazaki. There is no doubt for a second looking at the animation, as a fire rages in Tokyo, who the director of the film is. Similarly "Miyazaki-en" is the appearance of young Mahito and his father, as the latter dashes out into the city to hopefully find Mahito’s mother. The framing, the architecture, everything is comfortably Miyazaki and yet fascinatingly he brings something new. As Mahito refuses to listen to his father and too runs out into Tokyo ablaze, there is a visceral rawness to it, reflecting the violence of the fires, that feels more real, more personal than anything I can recall in a Miyazaki film. It’s no surprise then that most of the plot points are pulled directly from his own childhood, even the timings with the war click into place. You really feel how Miyazaki is exploring his own memories, real or imagined, looking into his own past. The jagged blazing inferno and chaotic maelstrom of desperate people and a young boy is brutally affecting. As an opening it may be one of the best Miyazaki has ever put on screen and yet it’s never overplayed, hitting you with breathless anxiety until it takes us into another very recognisable Miyazaki countryside, populated with pantomime women with exaggerated features, bulbous red noses and playfulness. But again, even here the war intrudes, as Mahito’s father sends food you realise how this large estate has little there in way of provisions or even tobacco. There is also some more emotional rawness, as Mahito is introduced to his new mother, Natsuko, whether with warning or not we never know, in a moment of delight, Natsuko presses the boy’s hand to her midriff and announces she is pregnant - and as an audience we feel both her delight and also recognise how emotionally the child is being ignored, unprepared, and we are asked to recognise the complex emotions behind both characters and see the divide there.

The ladies of the house (and their supplies - corned beef!)

For Mahito is an outcast, at home, at school, even taking to measures that again illustrate the boy’s emotional distress in ways that you might not expect from Miyazaki and so he, in many ways, subverts many of your expectations.

Then the heron really intrudes, subtly changing from a graceful creature to something more menacing, threatening and grotesque. Is this all in Mahito’s mind, or is this real? Certainly for a while there is a great doubt as to what is real and what is not, until finally, Mahito, upon a search for the suddenly missing Natsuko, is plunged into a fantastic underworld.

And with this we are perhaps in more recognisable Spirited Away or Howl’s Moving Castle territory, and Miyazaki’s imagination is front and centre, for you cannot deny how he manages to fuse humour and the occasional grotesque into a beautifully created world. It's replete with much of what you might expect, including arcane devices, wonderfully realised areas, each populated with its own set of characters and clearly defined reality and architecture. It’s gloriously done but is not perfect. Mainly because this fantastical world feels a bit fragmented, it lacks the coherence of his most cleanly created worlds. Visually it’s a sheer treat in so many ways, from the literal animation to the structure of the designs to the characters human or anthropomorphic. But the world itself feels a bit woolly in terms of what it actually is. It’s evident in how he has often to suddenly introduce something. A person, idea or concept. It never feels as fluidly real as say the world of Spirited Away, which needs no explanation. Whereas in The Boy and the Heron for too long feels like the fantasy world is a series of moments, of vaguely connected places, that do finally come together but it never feels fully cohesive. There is an argument that the end of the film makes this lack of obvious cohesiveness meaningful. But even if so, the way some characters are introduced feel a bit too "deus ex machina". Thematically these moments often make sense, but they feel a little bit too out of nowhere too often to make Miyazaki's latest world translate to screen as effectively as one might like.

That said, I was forever aware of needing to watch the film again. To see if a second time I would feel the same way. There is another aspect, which is even if the fantastical world feels a bit too much a series of moments, it is nevertheless far, far better realised than almost any other director might hope to do so. I mean, it blows the overblown Belle out of the proverbial, and the quality of the animation and the thematic resonance of the fantasy world are impossible to deny. As I noted, how the world is presented, especially the parakeet sequences (I know I’ve not mentioned this and I shall say no more) are beautifully realised, in some ways some of Miyazaki’s best work in isolation.

As a film The Boy and the Heron thrills because it shows Miyazaki able to really stretch himself artistically, even if sometimes he falls a little short. But in this, he falls a little short of his own best work, not by anyone else’s standards. His high bars are like Kurosawa trying to top Seven Samurai. Just how do you do that? Certainly, the emotional complexity and the occasional distressing emotional rawness shown in Mahito's character felt unusually down to earth, as does the visceral inferno in Tokyo. Yet underscoring this is what we expect from Miyazaki in a story of a young child learning to find friends through adversity, experience; emotional growth and the stretching of wings towards becoming an emotional adult is clear here as always. There is also the trademark Miyazaki moment of inventing creatures that are affectionately warm, but which in another film would be schmaltzy-cute.

Approaching 80-years-old as the film was being progressed it’s unsurprising Miyazaki looked back to the past, but the animation seems to look forward, being as fluidly thrilling as you would expect of the master with his own recognisable designs. We should be glad for this film and hope that, if rumours are correct, we can look forward to at least one more opus from Hayao Miyazaki.

So when the film releases in the UK on December 8th, get out there and watch it. I definitely need to see it again, because I feel this is a film that you need to allow to settle in a while, to test the waters of it. Some moments I loved, even when at the most raw: those opening shots of the Tokyo inferno felt physically and emotionally visceral, and maybe one of the best moments of Miyazaki’s career; just as some of the structure of the design when we move into the fantastical world equally carried such quiet and carefully designed humour that it was impossible not to smile.

And beneath it all the thematic richness and emotional arc of Mahito, which as we expect with Miyazaki is never overplayed.

Oh and I really do think that the Japanese title: How Do You Live? is more resonant, shame the powers that be felt us Western audience couldn't handle it.

The Boy and the Heron releases nationwide on December 8th.

Yes, I really was this far back...

Yes, I really was this far back...

Long-time anime dilettante and general lover of cinema. Obsessive re-watcher of 'stuff'. Has issues with dubs. Will go off on tangents about other things that no one else cares about but is sadly passionate about. (Also, parentheses come as standard.) Looks curiously like Jo Shishido, hamster cheeks and all.

posted by Caitlyn C. Cooper on 25 Feb 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 17 Feb 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 13 Feb 2026

posted by Caitlyn C. Cooper on 02 Feb 2026

posted by Caitlyn C. Cooper on 31 Jan 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 30 Jan 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 27 Jan 2026