Written by Alexander Smit on 27 Nov 2015

Hayao Miyazaki is a titan. There are few that would consider themselves a fan of anime without having seen a single one of his films. Those that have, indisputably should. In the West, he is perhaps the art form’s greatest legend and favourite grumpy grandfather. I say these things because they help us understand the scope of the man around which this film revolves, for whom it will most likely be the last feature-length production he is ever responsible for.

The Wind Rises can of course be simply viewed as the story of one Jiro Horikoshi, creator of one of the deadliest warplanes ever to fly, but that would do a disservice to both the film and to the extent that its director put himself into the film. Jiro in the film, for all subtextual intents and purposes, is Hayao Miyazaki. From that, it becomes a lot easier to unpack what Miyazaki has to say about art and about himself.

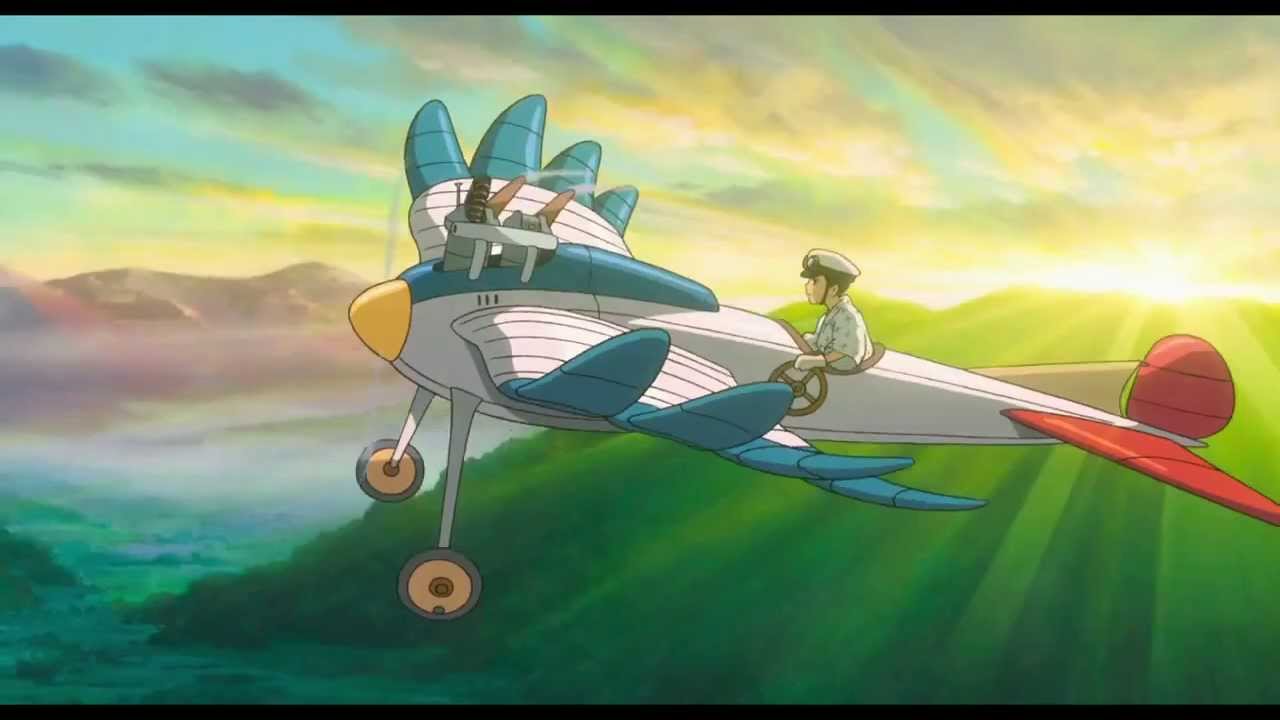

We are introduced to planes not as killing machines, but as dreams and objects of wonder. The first scene of the film is a dream Jiro has, in which he flies a plane from the roof of his house, from the night into sunrise. The mandolin and accordion music accompanying the scene inspires romance and reminds us of the other film in which Miyazaki may as well have been the protagonist: Porco Rosso, also starring warplanes. The world is so gorgeous as to make accomplished impressionist painters weep, when seen from this plane. The shadow of the plane covers everything below it, being far more important to the dream than anything else. Yet even in this fantasy, young Jiro is aware of the spectre of war. In what is some unsubtle foreshadowing for the rest of The Wind Rises, Jiro’s dream is hijacked by fire and death in the shape of enormous airships.

The planes of The Wind Rises are art, in the literal sense and in what they represent. They are dreams of the artist-engineer, whose sole purpose is to make them a reality. There is even an uncomfortable moment where his imaginary projection of another engineer, who functions as a spirit guide of sorts, tells Jiro that all artists only have ten years of productivity in them (Miyazaki has been working in animation for at least four times that). This guide, Caproni, tells him to get to work.

Again and again, Jiro is made aware of what his planes will be used for. Even this film is frank about that: most that fly Jiro’s planes will not survive and many more will lose their life by their doing so. Jiro imagines hamlets on fire, he sees the squalor in which his countrymen live while his government spends all its funds on the war effort, and he experiences the contempt with which his German allies treat him. Yet every time, a wind brings blue skies and the pristine, white idol of Jiro’s plane-to-be to Jiro’s imagination and to the minds of those in his presence; so Jiro works on.

The inevitable happens, as it tends to do: Jiro finishes his Zero fighter, the planes go to war, and none of them come back. In his mind he imagines a graveyard to his life’s work, endless stories high, mangled and burning. Jiro walks toward the light and the graveyard turns to the familiar green field and blue skies of his dreams. Caproni is there to meet him, to remind him that this was always going to happen, but that it was worth it. His dead wife, Naoko, is also there, telling him to live on, right before she fades away. The wind rises again, the engineers go to have some wine; they fade away too.

Author: Alexander Smit

posted by Ross Liversidge on 17 Feb 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 13 Feb 2026

posted by Caitlyn C. Cooper on 02 Feb 2026

posted by Caitlyn C. Cooper on 31 Jan 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 30 Jan 2026

posted by Ross Liversidge on 27 Jan 2026

posted by Guest on 24 Jan 2026