Written by Richard Durrance on 14 Apr 2022

Distributor Third Window Films • Certificate 15 • Price NA

As Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle opens, what first impresses you is how many production companies were involved in the making of it, the screen slowly filling with the name of company after company, which suggests serious intention and serious difficulty in getting the film made. So, was it worth it?

(Spoiler alert: yes.)

Recruited into special intelligence training, Onoda is then sent to a small island in the Philippines towards the end of World War 2, with the orders to "hold out", which he duly does... for the next thirty years.

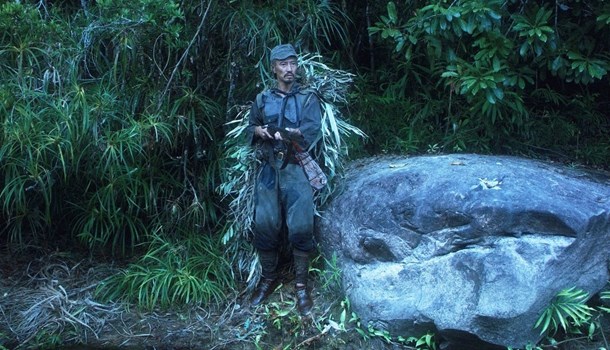

The narrative is roughly drawn from a true story and I’ve not dug into where fact and fiction meet, though watching the film you can work out some elements of fiction unless real life coincidences really are stranger than fiction. But certainly, in director, Arthur Harari’s film, Onoda does not survive alone. Arriving as the American forces begin to shell the island, Onoda is pretty much entering a form of hell. His commanding officer is ill, his fellow soldiers exhausted, injured and wanting to go home. Onoda finally formulates his hit & run strategy while living in the jungle strategy alongside his second in command Kozuka, and for a time foot soldiers Shimada and Akatsu. These are the few who are left on the island and decide to live by the code and orders of their commander. Onoda himself seems an intriguing character, a delinquent brought into the intelligence division by a major who recognises something special in his unorthodox mindset. You may suspect that Onada's refusal to follow many of the traditional social norms is based on a purity of individuality, self-reliance and perhaps, ironically, a very conventional mindset.

Some reviews have described Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle as an epic film, a description that seems erroneous to me. The film is long, at nearly 170 minutes, but the length of a film doesn’t mean it is epic. In part a definition of epic is a celebration someone who performs heroic feats and Onoda: 10,000 Nights recognises the absurdity of Onoda’s situation too acutely for it to be an epic film. If anything, the film aims to balance its respect at Onoda’s sense of duty and his remorseless, sometimes bewildering determination with an acceptance that it is also a metaphor for the futility and the absurdity of war. It is also a description that ignores that this is often a very intimate character driven piece, understandable when much of the film is no more than two to four men sharing small spaces in a jungle, and then are often in conflict with one another.

The film does not present Onoda, or as it often is Onoda and Kozuka, as hero or villain and if anything refuses to make any moral judgements. This you can argue is in the film’s favour because Onoda’s methods are understandable in the context of desperate wartime, but not in peacetime. He is given plenty of evidence that the war is long past, but his sense of duty keeps him sticking to his mission. This is a tricky situation narratively because how can we believe that Onoda would go on, sticking it out year after year, decade after decade, when almost nothing short of insanity would suggest a person not accept that the war has ended? This is actually nicely handled in the end, with Onoda and Kozuka misreading and misunderstanding what they learn, and you suspect recognise that the war has ended but need to justify that they have not surrendered, developing bizarre narratives around what is happening in the outside world and importantly their potential importance in an ongoing war. They feed on Onoda’s training, finding fake codes just like you might look for signs and portents in tealeaves: always there if you look hard enough and want to believe. You can understand their blind devotion to false narratives that, without which, their house of cards fantasy war and absurd obedience would be for nothing. It's entirely conceivable that they could not emotionally handle such a betrayal of their training and the ultimate waste of their lives.

Mapping the island unaware of the years to come

There are tougher messages in the film, too, because Onoda and his soldier’s actions have a deadly impact on the island’s native Filipino population. If the film has one glaring shortfall, it would be that it doesn’t really investigate this too deeply, and where you can squarely argue Onoda’s actions and orders were immoral and criminal (though the film does point out they are not criminal in the context of him still understanding that the war is on) though I suspect this is intentional on the basis of the film is not looking to point fingers but present a story of a remarkable set of circumstances.

Hatari does not forget that this situation is absurd and is not unwilling to play out that absurdity (arguably how Onoda returns from the war is random enough you suspect it’s genuinely mostly true) as well as playing out the conflict between all the soldiers and investigating their closeness.

This is a compelling film and much of the attraction comes from the intimacy between the characters and directorial choices as to how the narrative is told. The film is unafraid to skip years at a time, without reference to in-between periods, something that provides us a sense of the remorselessness of their survival but also how much of what seems remarkable to us is every day for them: their constant travel through the jungle from rough built shack to rough built shack seems unthinkable. It also means we need a young and old Onoda and Kozuka, the casting really fitting together nicely, and each actor providing compelling performances. For me, the real star, though bookending the film, is Issey Ogata as Major Taniguchi, who brings Onoda into the intelligence unit. As we're shown Taniguchi’s training of his recruits, often taking the form of oblique learning, this is what makes us believe that the delinquent Onoda really would stick it out in the jungle and even allow himself to invent ludicrous narratives to allow himself to continue and accept the actions and decisions he has taken.

I found it interesting how, for the most part, the director captures moments of horror in the film in an almost third person matter-of-fact manner, allowing the situation to explain itself, whether the shooting of innocents or the dying of soldiers from unknown diseases; though Harari infuses certain specific moment of personal violence with a sense of chaos even if he is never able to duplicate the visceral punch of, say, Shinya Tsukamoto’s recent adaptation of Fires on the Plain, though you suspect Harari does not intend to go so far as Tsukamoto is willing to go. Both are telling different forms of stories but both involving war.

For all that the film nearly touches three-hours it never feels long and there seemed to be little fat on it at all. Only one short semi-dream sequence seemed in anyway superfluous. It’s not without humour but much of that is on the bleak side, understandable considering the nature of the story. The impact of the film is definitely enhanced on the big screen, the woomph of American guns and the city burning early on in the film hits harder when the sound physically hits you, while later in the story the sounds of the jungle surround you. For all this, you stay for the characters and their stories, and Onoda, Kozuka, Shimada and Akatsu are distinct and interesting people. Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle manages to slowly make its way under your skin.

Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle is on limited release in cinemas from April 15th and Blu-Ray and VOD from May 16th.

Long-time anime dilettante and general lover of cinema. Obsessive re-watcher of 'stuff'. Has issues with dubs. Will go off on tangents about other things that no one else cares about but is sadly passionate about. (Also, parentheses come as standard.) Looks curiously like Jo Shishido, hamster cheeks and all.

posted by Richard Durrance on 06 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 05 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 02 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 25 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 12 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 10 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 07 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 03 Feb 2026