Written by Richard Durrance on 17 Oct 2022

Distributor Third Window Films • Certificate 15 • Price £79.99

Nobuihko’s Obayashi’s House is a rare film in that it is both much admired in the UK and also frequently available, thanks to those fine folk over at Eureka. The sheer audacious artificiality of it hits certain kinds of nerves. I have one of those nerves, one similar to Seijun Suzuki at his best where regardless of what the film is ostensibly about, what we as the audience see is something quite different. So though Obayashi’s anti-war boxset sat in the "to-watch pile" – I know, I know, this is not good - one luxury for this reviewer is it forces a certain immediacy, knowing you need to review a film, or in this case, a set of four films, which pushes this oft indecisive reviewer into action.

So it was that I watched the four films comprising Third Window’s Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 80s Kadokawa Years boxset. So what are you getting? Let me help you with that:

School in the Crosshairs (1981)

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (1983)

The Island Closest to Heaven (1984)

His Motorbike, Her Island (1986)

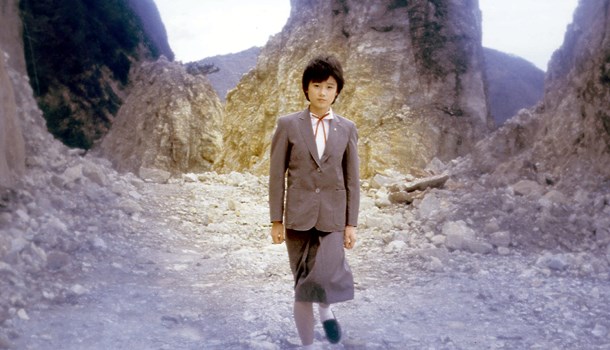

Starting with School in the Crosshairs, it’s not unfair to call it a noble effort. The story of psychic high-school girl, Yuka, her friend and Kendo captain, Kouji, whose school is aiming for the highest possible grades and is not in the least interested in physical education, despite the protestations of PE teacher, Yamagata. Class swot, Arikawa, wants the attention but Yuka is the star pupil and beloved in her class; only then enters Michiru, who like Yuka has power over events and people. So it is that a power struggle of galactic proportions sets Yuka’s high school in its crosshairs.

Those lucky enough to be charmed by Machine Gun and Sailor Suit (1981) will welcome the return of Hiroko Yakushimaru as Yuka, though she hasn’t quite as much to work with, nor at 90-minutes is the film quite as consistent as her other cinematic treat. It’s a shame, as the film open as you might expect from the director of House, full of stylistic energy, meshing saturated colour, eerie visuals and black and white fades, into a film that is a pleasure to watch while also narratively intriguing. As Yuka saves a child, turning back time, we wonder quite what is happening. We only know so much, though much of the introduction really factors into introducing the main characters, yet as always Obayashi keeps us stylistically hooked. Yamagata, when berating the head teacher for ignoring the physical side of their health, smacks the head teacher’s desk, causing three figurines sat there to jump consistently and continuously in a visually comic motif. It’s a small thing but an attention to visual interest that ensures that as a viewer we’re always given something that goes beyond the rather pedestrian melodrama of much of the script in this, yes, teen film. The humour also ensures that the earnest nature of the moment never becomes trite.

Equally, shortly after this the new intake of students are brought into the threatening throng of being induced to joining a school club! It’s a vibrant music video of a sequence full of visual energy and is hugely engaging. It gives a visceral sense of being a new student, alone and utterly overwhelmed and unnerved. It could be so by-the-numbers, but Obayashi wrings out all he can from it, crafting a dynamically entertaining sequence.

Unfortunately, the film narratively struggles to know quite where it wants to go and though elements of it are all appropriate, it reaches the difficult 30 minutes in stage where it stutters, not sure of quite where to turn next. You feel minutes should have been shaved off the film, because it meanders a while, awaiting the introduction of Michuro the psychic, and the film starts to take off again, becoming first a fascist allegory until Obayashi is then let loose on the denouement, a sequence that like the introduction milks all it can from the limited budget, being a visual feast of garish early-80's special effects that are also narratively important. It’s brash, bright, utterly unreal but unashamedly enjoying itself. It’s a great ending, even if making the narrative stutter in the middle seem more unfortunate.

The film bounces between sheer ludicrous madness and trite high-schooler story-telling and at its height is wonderful to behold but at its worst treads water. Yet Hiroko Yakushimaru as Yuka has a charming presence, though perhaps best is Masami Hasegawa as the would-be school fascist leader, Michiru, because she is the one character who really gets to have the most stony-faced fun.

All that said and done, it made me intrigued to watch the next film, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time. Though I had seen the 2006 anime film by Mamoru Hosado, if nothing else, School in the Crosshairs had at best a visual inventiveness that belied its likely means and so that boded well for The Girl Who Leapt Through Time.

Intriguingly then though The Girl Who Leapt Through Time opens using a similar technique that Obayashi uses in School in the Crosshairs, of fading to black and white, focussing on splashes of colour, often to emphasise the subjectivity of what is happening to the characters. His follow-up film is far more restrained and all the better for it. Not that I have any issue with the stylisation of the first film in the set, rather The Girl Who Leapt Through Time illustrates Obayashi's capacity to adjust his filmmaking to the content. It is not unfair to recognise that he has a better story (and I suspect script) to work with, one that allows the narrative to unfold more delicately and often you don’t realise how well written the film is until the end. How much of this comes the novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui I cannot comment upon, but it’s a beautifully paced film because in many ways not a great deal happens, rather it allows the story and the character of Yoshiyama, the titular "girl", who suddenly finds herself shifting subtly through time, after an accident cleaning the school lab, and her relationship with two friends: Fukamachi and Horikawa, both of whom she feels affection for.

The difficulty of describing the film is because it does so much so well. It contains drama but it is never overly dramatic - if anything the story and the emotions that come to the fore are all underplayed. It is this more adult approach compared to the more teen approach used for School in the Crosshairs that really elevates The Girl Who Leapt Through Time. It trusts to an audience being able to read what is happening on screen and also accepts that as a viewer we may be at times a bit confused. Yoshiyama seems to fancy Horikawa but then Fukamachi and then it all comes together; what may initially seem bewildering is narrative necessity. The beauty of the storytelling is that the narrative understands exactly where it is going so it never feels confused, rather that we are being manipulated but in a good way, because you intuit the film understands what needs to happen, rather than with School in the Crosshairs, where it loses its way mid-narrative. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time knows exactly what it is about. It drip-feeds us information knowing when and how it will pay it off.

Other advantages are perhaps less clear but nevertheless apparent. The cinematography is surprisingly good, so that when Obayashi’s more signature cinematic artificiality and use of brash colour is less common, it is still visually lovely. The film makes the most of its small-town setting, and many of the homes are architecturally fascinating. They are awash with steps and confined spaces filled with muted colour and often the film has the shimmering loveliness of a film shot by Joseph Walker in the 1930’s and those that have seen those will know that is in no way a small compliment.

The story and the characterisation give greater space for the actors, and Tomoyo Harada as Yoshiyama really deserves credit because it is rare that there is a moment of the film where she is not present. More than with her two friends, the film arguably stands and falls on her. If we don’t believe in her emotional reaction to what is happening, or feel it is over-reactive or... [insert your preferred definition] then everything rather falls apart. But Harada underplays just as the film needs her to, but she also feels like a real person.

Honestly, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time was a much better film than I expected. It was a surprisingly mature, delicate work. That said I think it is fair to say that the epilogue element to the story that you suspect is drawn from the source novel is entirely superfluous and I for one would remove it because at that point in the film, you know in your own mind what is going to happen or not and being explicit, even in passing, adds nothing. That said this is mere picking at the surface, finding fault perhaps because all the rest is so surprisingly good though I was thinking that the film would likely be overlong, though an hour and forty-five minutes, because it didn’t appear that it could sustain itself but it did.

Intriguingly, having watched Hosoda’s film some years ago and never since feeling the need to rewatch it though owning the DVD, I suspect I’ll return to Obayashi’s film, to see if the second time round if it is as efficacious.

It’s not unfair to say then that The Girl Who Leapt Through Time set up even greater expectation for The Island Closest to Heaven, which starts like a 1940-50's American melodrama, with a lush dreamily orchestral soundtrack that washes over a frame on a beach and, as the credits roll, they do bottom up, designed like a film of the period. Intentional? I’d think so! It does have the feel of a 50’s melodrama, especially in how they often dealt with characters finding love in exotic locations and the film plays out almost like the inverse of David Lean’s Summertime.

Having grown up with fantastical stories of a place closest to heaven from her father, upon his death the now teenage Mari is allowed by her mother to take a tour to New Caledonia, where her father told her that the place closest to heaven resides.

It’s not surprising that The Island Closest to Heaven is a film about finding love and finding yourself, not just the nearly 17-year-old Mari, but those she comes into contact with throughout. Like almost all melodramas The Island Closest to Heaven is intrinsically a morass of tropes smashed together, and like the best melodramas it makes of those tropes something so much better than you have a right to expect. Stylistically it is much more subdued than either previous film, though Obayashi does use some amount of fading colour, especially in Japan in stark contrast to the bright, always sun-filled islands that Mari will visit. During her trip Mari meets - and sometimes changes the lives of - a rogue's gallery of characters, many of whom in a different film could feel very different indeed. In fact, the film could have played out very differently. When first leaving Japan, Mari is sat next to someone else on the tour, loudmouthed, boorish, physically intrusive, the very antithesis of the person you want to be sat next to not just a plane, but anywhere; this matters in as much she is a counterpoint to quiet, determined Mari, who instead of following the tour she takes off on her own, and more often allows fate to point her towards other places off the beaten track both literally and emotionally.

Whether this is with the elder man, Fukaya, a guide who at first seems like he might be some slimeball sleaze wanting to get into a 17-year-old's knickers, or helping a visiting essayist rediscover love, Mari finds herself on a journey that is out of her control, but which she also bravely guides. What hits you is the sheer good-naturedness of the film. Fukaya really isn’t a sleaze, he could be, but instead like almost everyone we meet has his heart absolutely in the right place, if not on his sleeve. The stream of characters, all so bloody nice in many ways, could be saccharine sweet to the point of inducing diabetes, but it’s always balanced with bouts of reality: the tour guide who is frustrated by Mari’s individualistic single-mindedness or the reality of the boy she meets, Taro, whose life is too different from hers, or being stuck alone and without money trying to check into hotels populated by men you’d not want to meet down a dark alley. But much of why the film works is that Tomoyo Harada as Mari carries the film with a mix of wonder and determination. And that’s no easy feat considering it is in many ways a two-act film, split almost exactly into two fifty-minute sequences.

The first act draws to a close with Mari’s trip supposedly at an end, before circumstance causes her to veer into a more freewheeling adventure. Yet throughout both acts, her story is captured in those around her, and the side stories themselves carry quiet emotional power and resonance to her own adventure, which ensure that the film never starts to feel over-extended. Unlike School in the Crosshairs, that felt like a sixty-minute film extended out to ninety because of the muddled middle period, at the moment where The Island Closest to Heaven could have come unstuck if anything it finds its feet the best.

Honestly, as the film began, I didn’t have high hopes for The Island Closest to Heaven, but it’s tonally spot on all the way through and like some of the best melodrama it’s so damn hard to say why it works. Unlike Douglas Sirk’s 50’s melodramas it doesn’t push boundaries but like Sirk, Obayashi’s film ingratiates itself with you. Though a teen film, it is nevertheless universal and so deserves more attention than it has had. Arguably in the context of the first two films in the set, the lack of obvious style illustrates Obayashi's flexibility as a director. Admittedly like The Girl Who Leapt Through Time it is backed up by a strong script.

So the set being ever on the incline, there's one film left: His Motorbike, Her Island.

Drum roll.

Tension.

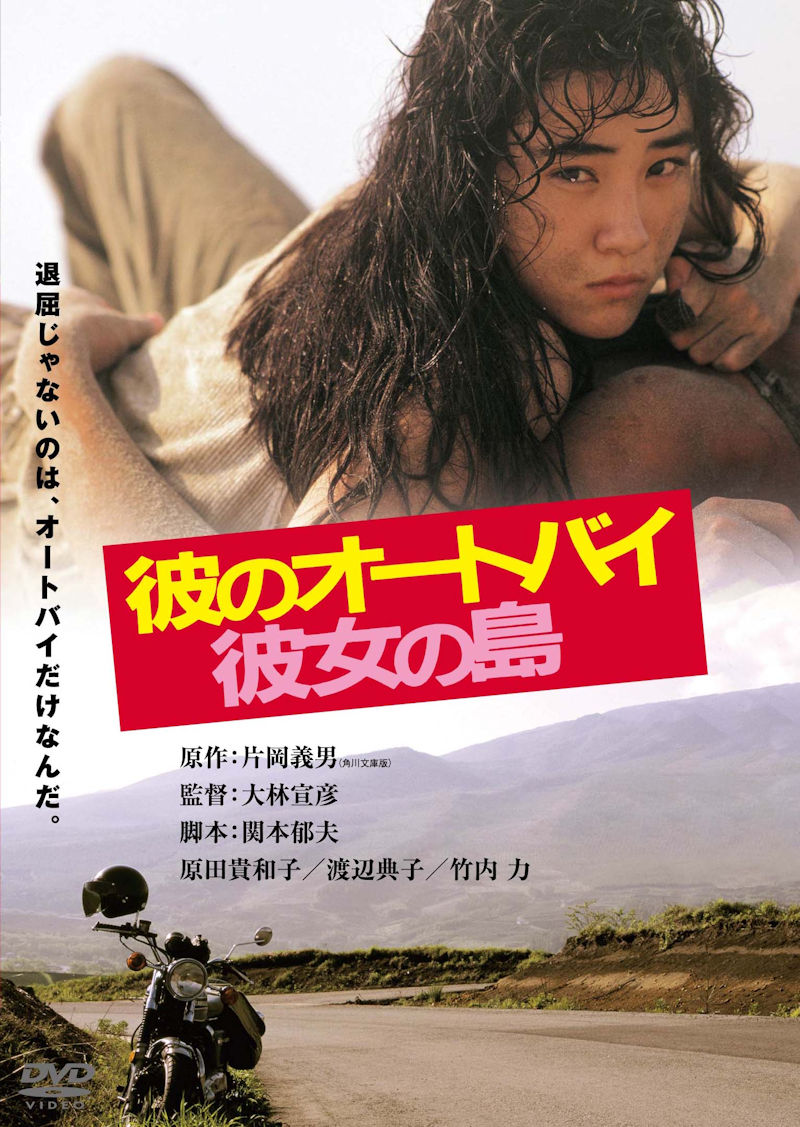

More black and white opening credits, but this time visually truncated to small views of the world, bold and fast-paced, reflecting the biker energy of bad boy, Ko, who is then leaving town to get away from the brother of his ex-girlfriend, Fuyumi, who has taken issue with Ko’s ditching his sister. Along the way Ko meets Miyoko who wants to ride his bike... and so starts a romance between a man, a woman and a motorbike.

On paper this is yet another teen movie, though this one is a little different. This in part because our protagonists are not teenagers but adults, in their early twenties and so whereas the earlier films are more innocent in terms of sexuality, His Motorbike, Her Island most definitely is more sexualised. Early on, as Ko leaves town and waits at the lights, how he caresses his motorbike evokes the kind of homoeroticism of a Kenneth Anger short film, intentionally or otherwise. Regardless, it sets much of the tone because the eroticism throughout is often focussed on that throbbing machine between one’s legs. And yes, I do mean a motorbike... probably. Also, not only is there a lot of sex bubbling on beneath the surface there is also (shock, horror!), actual nudity. Actually, quite a lot, but how it is approached is rather interesting, because it is both eroticised and not; rather it is reflective of two people who are attracted to each other but also casual. There's no prurience here.

Not that my main takeaway is nudity, but the manner of how it is handled - also it's as a likely to be male as female nudity feels unusual and sets the tone for the film; because really, though the film is an adult romance, on various levels, it is a film that deals with a man and a woman and their love of bikes and each other – but, yeah, bikes mostly. And, curiously, despite the film's opening where we might expect more violence, and despite the fact we get jousts on motorbikes (shades of George Romero’s Knightriders perhaps?), it’s more in line with The Island Closest to Heaven that most of the characters are surprisingly benevolent. Yes, they may sometimes be casually violent, but this seems an aberration, a mistake of youth rather than any particular desire to do harm. It is well-adjusted people in moments of maladjustment.

Yet it’s not unfair to say that as the film opens, Obayashi's stylistic movement between black and white and colour is for a while a distraction. Not visually, because I love black and white and the shifts work well on an aesthetic level, but because Ko tells us in the voiceover that he dreams in black and white and so there’s a series of scenes where you struggle to understand if what you are seeing is meant to be dream or reality or past or future or imagination... when really more than anything it is just style and Ko’s description of his dreams is, if anything, a distraction; then as the film unfurls you recognise that it is sheer style and enjoy it as such. And to be fair, as style it works beautifully, it really does so that once you go with its flow and realise it’s not doing anything obviously deeper you accept that Obayashi is having tremendous fun, as often he is with the scenes on the bikes that never fall into tedious bike porn, careful to keep a tab on the characters and their dynamics, most of which feel fleshed out even when we meet characters only in passing.

Arguably the narrative does lack a certain amount of focus, unlike the films that centre the set, and yet that is never an issue because the films breezes through its 90-minutes. It’s perhaps not a classic but that’s OK, few films truly are, but it’s far more artistic and interesting than it could have been in other hands. Many of the scenes on the bikes show real panache, but again they also have visual flexibility because it handles the dark night bike jousting just as well as it does the more freewheeling scenes on Miyoko’s island, as their bikes seem to dance around the island.

In keeping with many of the films, Kiwako Harada as Miyoko is perhaps the most magnetic figure in the film, but it’s hard not recognise the sheer physicality of Riki Takeuchi as Ko, even if he is hardly quite as visually impactful as his intentionally grotesque character in Tokyo Tribe some decades later. There's also some real chemistry between them both, though in many ways I found myself drawn to the small role of Fuyumi, as initially Noriko Watanabe as the ex-girlfriend is a bit drab, though she gets to have a real transformation even though she’s only in a handful of scenes.

Coming to a boxset like this Obayashi Kadokawa 80’s series is always a little bit of a nervous moment. I know how I am, I can very easily within minutes just drift off into teeth gritting irritation. Not that I want to, that is the irony. More than anything I want to fall in love and did I here? No. But wait! Why would I? Honestly there are few films I think where you instantly fall in love, but instead I was treated to a series of four films that illustrate various aspects of Obayashi as a director and in some ways they are more fascinating for those moments that are more distinct than the better-known glorious artificiality of House, because it makes me realise how Obayashi could easily be a one trick pony but is not. It is true that School in the Crosshairs sometimes struggles when it doesn’t quite know where to go narratively, and in that film the story seems more important than the more knockabout narratives of the films that go after it. Also, one should not underplay how much of the photography from The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is often quite lovely, often in muted tones but beautifully crafted and these films with their HD remasters are great to look at. It’s not like early DVDs, where I remember my friend buying a boxset of Kinji Fukasaku films where it looked like you were watching them through twelve layers of gauze. Not good I can tell you.

I am not going to tell you that this is a classic boxset, one that will change your life, but it is a fascinating glimpse of films that could be so average but are so much better. And so, in a curious way, they nourish you, provide the poor audience with a greater diversity such that it can culturally enrich us. Long may Third Window release such sets of films - like they did in a different way with their Pink Films series.

I'm not sure what I was expecting. Maybe more films like House. But what I got was very different and I am glad for that, as even though not masterpieces, this selection of cinema illustrates Obayashi’s range even within a single genre. They show what is possible even when sometimes constrained and I was treated nevertheless to some very fine films I’d otherwise not have had the chance to witness.

Long-time anime dilettante and general lover of cinema. Obsessive re-watcher of 'stuff'. Has issues with dubs. Will go off on tangents about other things that no one else cares about but is sadly passionate about. (Also, parentheses come as standard.) Looks curiously like Jo Shishido, hamster cheeks and all.

posted by Richard Durrance on 17 Dec 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 12 Dec 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 09 Dec 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 28 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 25 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 18 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 14 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 11 Nov 2025