Written by Richard Durrance on 06 Jun 2022

Distributor Eureka • Certificate PG • Price £12.85

It was probably about ten years ago that I first saw the Eureka DVD release of Kwaidan. Honestly, it didn’t do as much for me as it should have, being touted as a classic of Japanese cinema, but with the chance to snag a blu-ray on sale came the chance to rewatch the anthology of ghost stories by Masaki Kobayashi, originally released in 1965.

The Black Hair: a penurious samurai leaves his wife to gain status in a new household, only to regret it and return to his wife, who may not be as young as she seems after so many years apart.

The Woman of the Snow: two woodcutters taking shelter from the storm become victims of a spirit, who takes the life of one and spares the other, Minokichi, as long as he never mentions what he has seen or else forfeit his life.

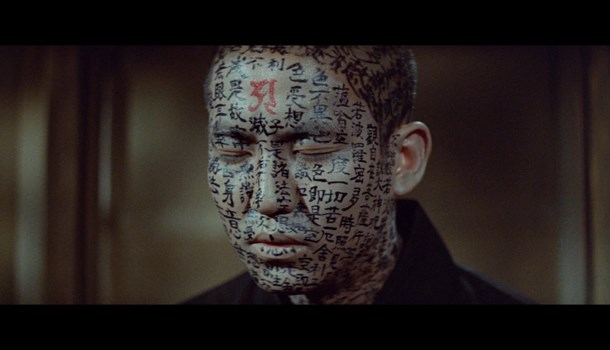

Hoichi the Earless: blind biwa-player, Hoichi, is taken by the spirits of the dead Heike clan, to have him sing the tale of their deaths; only for the priests in the temple to seek to save Hoichi’s life and soul from the dead.

In a Cup of Tea: a writer tells us a tale of a samurai, Sekinai, who consumes a bowl of water with the reflection of another man, only for this man to appear in his Lord’s home.

Anyone who has had the dubious please of reading some of my recent reviews may remember I’m generally not a fan of anthology/portmanteau movies, as they tend to be too short to really allow characters or stories to develop and revolve around twist or shock ending, most of which you can see coming a mile off. The stories in Kwaidan, developed from those collected around Japan by Lafcadio Hearn, are about as archetypal as you can hope for, and so characterisation often is limited. Some elements, too, are particularly recognisable to modern audiences – the black hair in the story of the same name will definitely ring bells with Ringu fans, or Sono’s Exte. But these aspects don’t matter too much because Kobayashi does not reach for any horror film in the conventional sense. At over 180-minutes, Kwaidan is clearly not your average film, and it is not really a horror film in the way that most will think of them. Instead it is a film that at most – like Dreyer’s Vampyr, the restored version of which I saw at the cinema the day before – it is out to cause unease and aims to create a more artistically vital piece of work.

As such I can understand why I might not have originally been a fan of Kwaidan. Not that I like horror per se, but because Kwaidan is a mood film, and a film where often you will need to be in the right mood to watch it. Like Dreyer’s Vampyr you have to allow it to envelope you in its eeriness. Also, for a horror film, Kwaidan isalmost stately in terms of its pacing and its framing. Each shot feels like a careful composition, and each camera track or dolly a very particular action. It’s never a fast film but is all the better for it because it creates a mood that is quite unique. This is heightened by the sets, all of which were hand painted and create a beautiful artificial world for the audience to enjoy. Sometimes this can be weirdly otherworldly, such as the eye-sunset shapes that cover the sky in The Woman in the Snow. It’s disturbing yet beautiful and its fair to say that most of the shots in Kwaidan could be framed on the wall, so love it or hate it (or just be generally disinterested), it’s hard to argue that it’s not a beautiful film. It does though have a certain almost Kubrickian exactness to the filmmaking, which heightens the artificiality, but again in such a way as to further the film’s artistic merit.

Layer over this the music by composer Toru Takemitsu. His music can be challenging to listen to but is used to beautiful effect in the film; often it is hard to distinguish sound effect from music as Takemitsu rarely uses familiar musical motifs, favouring percussive sounds to reflect the unease that unveils before our eyes. It’s hard to imagine a more unusual or a more fitting score to the film and feels far more necessary to the outing than many of the actors. This is not me bashing the performances, after all we have the likes of Tatsuya Nakadai and Takashi Shimura on hand, but because the stories are so archetypal this often this diminishes what is possible with their roles. Admittedly, Nakadai arguably gets the choice role of the woodcutter, Minokichi, in the story that has the most emotional resonance. That itself for some might be a problem, because many of the stories lack emotional depth, but the film is not particularly interested in creating it, being more embroiled in the creepy and painterly aesthetic.

It's fair to argue then that you should never watch Kwaidan as a horror film but instead as a work of art in its own right, and one which manages to eerily suck you in over its three-hour running time. It is sensible enough to have an intermission, remembering always Hitchcock’s statement regarding how a film should never exceed the capacity of the human bladder.

It’s rare to find a film quite like Kwaidan, it’s undeniably beautifully, sometimes otherworldly and very much feels like a singular vision from the director, Kobayashi, even though it is just as reliant upon Takemitsu’s score and the combined efforts of the art department to create such gloriously artificial and eerie sets. Yes, it is slow and precise in the extreme but that is integral to the pleasure of the film. I, for one, am glad I re-evaluated the film and will certainly return to it in the future.

Long-time anime dilettante and general lover of cinema. Obsessive re-watcher of 'stuff'. Has issues with dubs. Will go off on tangents about other things that no one else cares about but is sadly passionate about. (Also, parentheses come as standard.) Looks curiously like Jo Shishido, hamster cheeks and all.

posted by Richard Durrance on 06 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 05 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 02 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 25 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 12 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 10 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 07 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 03 Feb 2026