Written by Hayley Scanlon on 01 Mar 2012

Distributor Eureka Entertainment - Masters of Cinema • Certificate 15 • Price £14.99

Now, I know what you’re thinking and I’m sorry to disappoint you, but this isn’t a film about a giant half-woman, half-beetle stomping all over our favourite bits of Tokyo (although that is a film I would pay to see). Instead, The Insect Woman is rather a matter of fact study of one woman’s struggles over the course of fifty years of turbulent Japanese history. Drawing close parallels between the life of the protagonist and the fate of Japan in the post war world, director Shohei Imamura has created a dispassionate examination of what it takes to survive in this new and often cruel world.

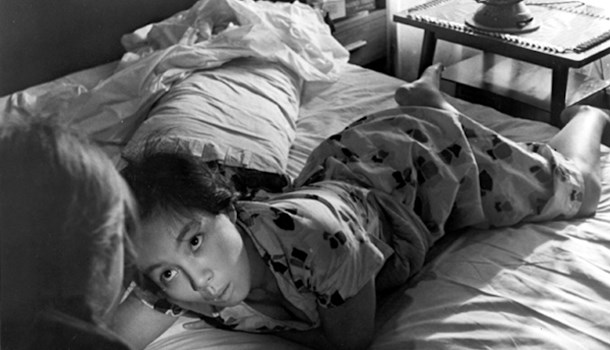

The film begins with Tome’s (Sachiko Hidari) birth in a poor village in 1918. Evidently Tome’s mother has been promiscuous and as she is unmarried the identity of the child’s father is unknown. However, the slow but kindly Chûji (Kazuo Kitamura) is convinced that the child is his and so accepts responsibility for her. As Tome grows the bond between her and the man who may or may not be her father continues to tighten. A series of vignettes cover her childhood until we find her again, working in a mill as part of the war effort. Her family call her home on the pretext that her ‘father’ is dying but really they intend to send her to work on a neighbouring farm as payment for a debt. Once there, Tome is raped by the younger son of the other farm owner and returns home pregnant. The pragmatic women of the family decide to let the (female) child die but Tome succeeds in persuading them to allow her survival.

From there, there's no other choice but to return to the mill to provide money for the child and the other members of the family. Wars only last so long, however, and Tome’s fierce unionism means that the mill isn’t going to be a long term option. It's off to the city then, and a position as a housekeeper for a GI with a small daughter. Again though, circumstances conspire against Tome and a tragic accident ends that chapter. From there she is unwittingly pressed into prostitution and ultimately becomes everything she so opposed in her youth. Nevertheless, Tome never gives up, never lies down and complains; she takes her opportunities where she finds them and makes the best she can out of the most difficult situations.

A more literal translation of Nippon-Konchûki would be something along the lines of An Account of Japanese Entomology and Imamura’s direction is indeed documentary-like in its approach. He shows us scenes from the life of Tome without bias or context, but simply as an illustration as if she were being studied under a microscope. Particularly near the end, Tome cannot really be described as a likeable character. She has betrayed and misused people once thought of as friends and may be about to ruin the life of her own daughter who seems to be continuing the saga of the women in this family. However, there is something truly captivating about her resilience and her determination to survive in the face of adversity. The shot of a beetle trying to climb a steep heap of dirt at the beginning of the film is echoed in the film’s ending as Tome tries to climb the steep muddy hill to her home town but repeatedly gets stuck, even eventually breaking her sandals. Tome and thousands of other Japanese women in her position are like insects - hardy creatures, desperately trying to survive despite almost insurmountable odds.

Implicitly, Imamura extends this metaphor to apply to Japan itself. Tome’s progress is marked by the invasion of important historical events into her personal story - notably, she always appears oblivious to or disinterested them. She misses Hirohito’s surrender speech because she’s so ill with malnutrition that she doesn’t have the energy to join the crowd listening in the hall, so she stays and talks with the man who had been her lover. Later she complains about the anti-security treaty rioting because it’s holding up her taxi and disrupting her business. These objectively important historical events appear almost irrelevant to her in her day to day life and she consequently pays them little mind. Yet, there is the subtle implication that like Tome, Japan has been mislead, abused and forced into prostitution but that like Tome, Japan is strong and will endure even though it may lose its soul in the process.

Shohei Imamura’s The Insect Woman is a key film of the Japanese New Wave. The unsentimental depiction of the fate of one woman, misused by men and fate but determined to survive, serves as a stark criticism of society’s unfairness - particularly towards women and the rural poor. Imamura’s camera is never judgemental, the characters and events are shown with a remarkable degree of evenhandedness but that doesn’t mean that the film is devoid of sympathy - a dispassionate eye does not explicitly exclude compassion. Strikingly composed, The Insect Woman is not always an easy or a pleasant movie to watch but it is certainly a very rewarding one.

Japanese monaural soundtrack with optional English subtitles. Also on the disc is Imamura’s 1958 film Nishi-Ginza Station (also in full HD 1080p on the Blu Ray Disc), a video conversation about The Insect Woman between Imamura and Tadao Satô and 36 page booklet featuring a new essay for each film by Tony Raynes

Available as a Dual Format Edition containing both DVD and Blu Ray copies of the film.

posted by Richard Durrance on 06 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 05 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 02 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 25 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 12 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 10 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 07 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 03 Feb 2026