Written by Richard Durrance on 18 Oct 2024

Distributor Radiance • Certificate 15 • Price £17.99

Director Toshio Matsumoto is best known for a film I’ve only partially seen, Funeral Parade of Roses (1969), a film I rented long ago and was in the wrong mood for and meant to return to all these years later, something I have failed to do but one day I will remediate this. Good then that Radiance’s fourth film in the month was his 1988 and final film, Dogra Magra, as this would allow me to make some small amends for my lack of funeral parade viewing.

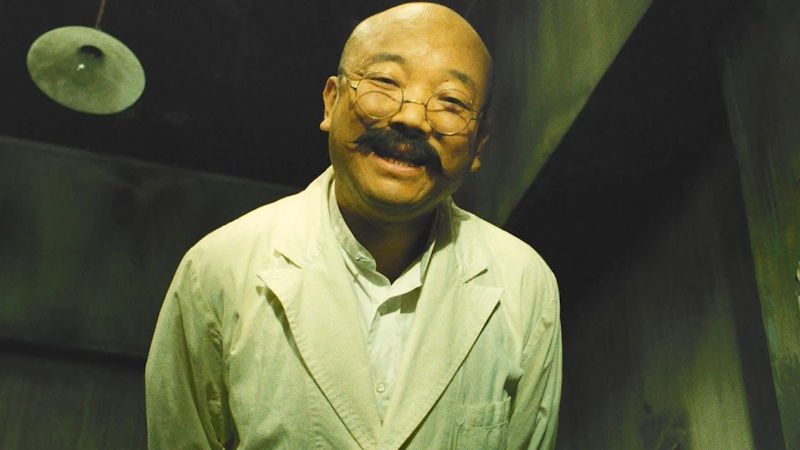

A young man, Ichiro (Yoji Matsuda), wakes up in a hospital cell to the sound of hammering walls, a voice calling and an empty memory. The voice is that of Dr. Wakabayashi (Hideo Murota) who enters and tells Ichiro of Dr. Masaki (Shijaku Katsura), the brilliant, perhaps brilliantly mad, doctor who treated him and the story of the artist to the Chinese Emperor who many centuries ago started to record a scroll to warn his Emperor of the intrigue around him, a scroll that caused the artist to murder his wife. This artist fled to Japan and Ichiro is perhaps a descendent who, in Dr. Masaki’s view, has gained his antecedent's genetic memory and sin.

Dogra Magra is a fluid film, a film of intentional cinematic artifice that sits in a dreamlike space somewhere between Seijun Suzuki’s Taisho trilogy and Pistol Opera, Guy Maddin’s Careful, Robert Wiene’s silent classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and arguably The Exorcist author William Peter Blatty’s first film as director, The Ninth Configuration, and yet is also its own special entity. I’m not a fan of using films to describe films but I felt all these works strongly when watching Dogra Magra. Some, like the lattermost of Suzuki’s trilogy, Pistol Opera and Maddin’s Careful were made after Dogra Magra, but the comparison is made more to evoke a sense of mood and also how these films exist as cinematic artistic entities. They have no interest in reality, instead possessing what I have always considered a narrative verisimilitude, that is no matter what occurs within, it makes sense in the context of the film, outside it, it may be ludicrous or unbelievable but such is the cinematic world created that here you never question it. For reference perhaps the best example of this in the last decade is Lynch’s limited event series of Twin Peaks – and if you are saying its TV, it was written and shot as a single film and cut into episodes so it’s a film in my book.) Dogra Magra shares this unique space and as such may be a bit of an acquired taste, but one you suspect will be enjoyed by those that love cinema in some of its more outre forms.

For the most part the film is three-hander and takes place within only a few areas but don’t let that make you think this is "stagey"; if the references above don’t make you realise that you are entering a cinematic world don’t fear because Dogra Magra is a deeply cinematic work. Often those images shot in the hospital have a slightly yellow, sickly glow, but it may then cut away to a deeply coloured, highly subjective image. Why? Because this is a dream of a film where reality, storytelling, history and memory, imagined or otherwise, all merge. Within the film Dogra Magra is also a novel, a story written at a single sitting by Dr. Masaki and it may tell Ichiro’s story, or does it dictate his story, or does his story even exist?

The importance of this is that they are immersed in the enigmatic nature of what we see; every moment we are forced to question what we witness, what we know; often the moment we believe we know the film, that moment the narrative tables are turned and then turned again, as a viewer we never quite get a handle on it all, even at the end, though there are some superficial knots tied. But that is the point, this is the kind of film where we should be questioning, experiencing, delving into what we see, hear and feel, and try and try again to build up what is unfolding, to re-evaluate and re-consider, to see it as being literal, subjective, you name it. It should be slightly untouchable and it is. Marry this to how Dogra Magra often is very willing to be intriguing, to use different methods to tell its narrative; the story of the Chinese artist to the emperor is told using a magic lantern show populated by gorgeously designed puppets to a record with a narration by our very own Dr. Masaki. It is all beguiling, mysterious, baffling but also compulsive.

One way to look at it is similar to Obayashi’s The Island Closest to Heaven (a surprisingly excellent film) where I remember halfway through thinking: where can this film go? About 40-minutes into Dogra Magra I had the same thought, not that I was bored but because I couldn’t quite grasp the film’s direction and sometimes this means a film will descend into an abyss of bullshit, but Dogra Magra definitely never does this. The one moment it seems to be straightforward it subsequently wrongfoots you. Its structure, floating effortlessly between reality, perceived reality, and fiction, is always effortless, and sometimes wonderfully subjective: Ichiro imagining himself a doctor and lecturing glides between pacing his hospital cell to an empty lecture theatre to his lecturing the inmates. By the end do we have answers? No, we have glimpses of answers and a view into the mind of our protagonists, but no clear understanding of how much we’ve seen is true. Not that this film needs truth, for it to have a single reading you suspect would be a weakness, the film’s strength is how each viewer could take a subtly different perspective on what has happened, on the aspects of manipulation of Ichiro in particular, on the fictional psychological conditions and methodologies used. Nevertheless some parts of the story are very much rooted in the narrative, there is much talk of doppelgangers and though these may or may not exist in the story, it is one that uses parallels throughout. The moment we see Ichiro asking for a mattock we remember parts of the story of the Chinese artist and a sense of dread creeps in as if he gets his hands on one, we know instinctively what must happen. But the why we can perceive differently: fate, mental illness, inherited memory, enforced mental illness... or a mixture of some or all.

Much of this disturbing mood comes not just from the visuals and performances, for this is cinema of creeping unease, but from the score by Haruna Miyake, often atonal, clashing and jarring. Like the visuals the sound has a precision to it that is carefully constructed to sometimes put you off balance but often to underscore the unreality of what we see. As noted earlier the film is often full-on artifice and can move into subtle surrealism, the photograph of Dr. Masaki on the wall suddenly talking, breaks into one of the more obviously straightforward scenes. Sometimes the film’s artifice seems almost invisible but it’s definitely there. Dr. Masaki frequently films his patients – and we should note the film is set in 1926, the end of Taisho period also the year of Teinosuke Kinugasa’s silent film, A Page of Madness, also set in a psychiatric hospital, is this an accident? - and when we see these films played back, they include intertitles, hardly something we could imagine the doctor would have spliced into it. No, these are like the moments of subjective silent film memory similar to those used in Kaizo Hayashi’s To Sleep So As To Dream (interestingly released two years before this film) if contextually very different and with a very different outcome.

One aspect very much worth noting is our three key actors, Yoji Matsuda as Ichiro, Shijaku Katsura as Dr. Masaki and Hideo Murota as Dr. Wakabayashi. Of the three Murota is likely the one you’ll know from countless films from the 70s into the early 2000s and his presence is absolutely necessary to the film. Katsura as Masaki often has a theatricality to him, I mean his moustache is theatrical enough!, not wildly so, but he has a doctor-genius-madness to his performance that you think is specific to the character, but it’s on the side of overplaying at times - and overplayed it should be - but it’s the kind of performance that needs balancing with a more down to earth, cinematic, underplayed performance and Murota provides that, with his easy screen presence, you would think born of spending so much time before the camera. The same for Katsura is broadly true for Matsuda as Ichiro; Ichiro after all is possibly mad, definitely amnesiac, and as much of his screen time is shared with either of the two doctors, so Murota again is necessary to balance out Matsuda’s outbursts. You can argue then the same is also true Murota for the character of Moyoko (Eri Misawa), who appears as Ichiro’s young wife, though her role is frequently requiring a certain sleeping beauty quality.

This is the kind of film I hate trying to score as often when trying to work out a numerical value I am doing so not against all films, but ones by the same director, perhaps those in a similar genre, or that are thematically linked. But Dogra Magra for all of my comparisons, and others that are possible such as late Obayashi for its artifice, is a unique vision, one that may divide viewers perhaps because this film is one that embraces cinema of the artificial and is unafraid to indulge its singular visual and tonal vision. It is as mysterious and unknowable as you could want it to be, yet controlled at the same time; it’s beautifully shot and occasionally jarring and you suspect cinema is richer for its release, especially in Radiance’s gorgeous print.

Long-time anime dilettante and general lover of cinema. Obsessive re-watcher of 'stuff'. Has issues with dubs. Will go off on tangents about other things that no one else cares about but is sadly passionate about. (Also, parentheses come as standard.) Looks curiously like Jo Shishido, hamster cheeks and all.

posted by Richard Durrance on 12 Dec 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 09 Dec 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 28 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 25 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 18 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 14 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 11 Nov 2025

posted by Richard Durrance on 07 Nov 2025