Written by Richard Durrance on 08 Sep 2022

Distributor Arrow Video • Certificate 15 • Price £18

Tomu Uchida’s (1898-1970) A Fugitive from the Past (1965) is regularly voted as one of the greatest Japanese films of all time in their homegrown press, yet this is the first release of the film in the West. With such a reputation at home and also being three minutes over three hours in length, approaching A Fugitive from the Past can be daunting. Also, the longer a film is often the better it needs to be, or else risk disinterest or at worst outright boredom. So, I put off A Fugitive from the Past for a few weeks before settling down to it. But the day came, well the evening anyway, and...

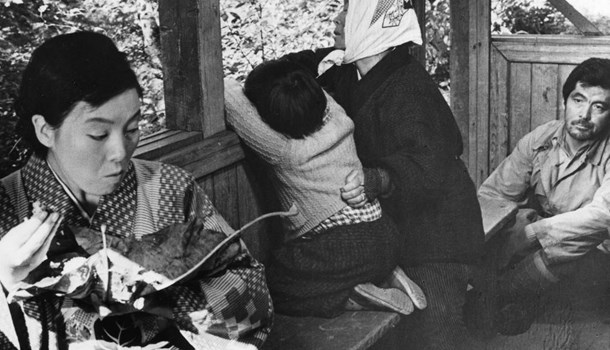

As a typhoon hits the Hokkaido coast, unbeknownst to the world three criminals use the cover of maritime rescue efforts to escape with their loot. On the day following the storm the police, finding two bodies not on the passenger list of a sunken vessel, begin to realise a crime has been committed, and that one of three escapees has probably killed the others. Taking shelter with a prostitute named Chizuru (Sachiko Hidari), fugitive Inukai (Rentaro Mikuni), wracked with guilt disappears but changes Chizuru’s life for the better, as the police search for Inukai, a quest that takes a decade.

Uchida’s filmography is extensive, dating back to the silent era, yet this is only the third release (that I know about) of his films in the UK, the others being two Arrow releases; Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji (1955) and The Mad Fox (1962), both of which are sitting in the dreaded to-watch pile. Uchida’s decades long directorial career in many ways makes A Fugitive from the Past all the more remarkable because it feels a very contemporary film when compared to other 60’s films, and not the work of someone who had made 70-odd films previously. Yet the grainy black and white cinematography Uchida uses seems entirely timeless, and also very fitting because the film being set just after World War Two, its graininess is entirely in keeping with the sense of underlying hunger, creeping poverty and quiet desperation that we often see, certainly in the early stages of the film. Yet Uchida does throw in some unusual stylistic motifs throughout, most often the use of the negative image, appearing to suggest a character’s subjective view, such as when the first detective we meet, Yumisaka (Junzaburo Ban), imagines what may have happened when the three fugitives were escaping over the water during the storm, or as Inukai plods exhausted and starving before he meets Chizuru. If the film had been shot in colour the conceit of using the negative image might have felt dated, but it works beautifully in black and white, being both disturbing and visually appealing.

But Uchida and A Fugitive from the Past seem most interested in the impact of the crime on the people who come into the sphere of Inukai. This should perhaps come as little of a surprise considering at the beginning of the film we know that Inukai is mixed up with criminals, there’s no suspense as to if a crime has been committed or if Inukai is knowingly involved in a criminal act, but the film very clearly differentiates him from his two friends. He does not rob nor kill the family but Inukai’s guilt at finding out what has happened is the emotional core of the film, making him a fugitive in a more metaphysical as well as literal sense. Yet his characterisation is not so simplistic, as we find out towards the end of the film. It’s this depth to characterisation that allows the film to maintain its three-hour length.

Honestly, at the ninety-minute mark I was wondering where the film had left to go and took me by surprise when it began following the prostitute Chizuru, as she starts her life afresh, or attempts to, though she seems obsessed with her lingering affection for Inukai. Again, Chizuru is not a paper-thin character, but one that cares for and, thanks to a surprise gift from Inukai, takes care of her family and friends who we realise are suffering the depredations and debt following the end of the war. Yet she is also intriguing, as there is something almost childlike about Chizuru, almost to the point where she seems to be emotionally stunted by her circumstances, perhaps not a surprise recognising that at an early age she had to enter into prostitution to help pay her family’s debt. It’s implied more than explicit if she is emotionally disturbed and it’s that act of piecing together her character rather than being spoon-fed information that keeps us interested. Chizuru could easily have become a rather trite cliché, but instead it feels like Uchida uses her character to reflect the impact of the war on the population, the emotional damage and yet also the hope that can come from common humanity and striving to work honestly, and, curiously, the dangers of it, as the ending of the film makes clear.

Though Inukai is the protagonist, much of the middle of the film (that time when many films start to fray around the edges or fall apart) is held together by Chizuru, and Sachiko Hidari’s performance balances the elements of her character beautifully. Upon reflection it would have been easy for Chizuru to have become tiresomely childish or excessively optimistic; she even manages the character's perverse fixation with Inukai’s years old toenail, which could be downright silly but instead seems very indicative of where her character is emotionally.

Similar complexity transfers over into Inukai, because he’s neither a wild criminal nor, as we later find him, entirely the guilt-ridden philanthropist. Instead, he’s a character of believable contradictions, haunted but also defiant and amoral. Yet Inukai is often defined by the impact he has on others, Chizuru most explicitly, but also his wife, the detective Yumisaka, who comes back into the story years later to assist the younger Tokyo based detective Ajimura (Ken Takakura). And how others react to him is emotionally believable because he’s not just some charismatic psychopath, in fact he's quite the opposite. If anything you suspect Inukai is ironically very humane but drowning in bad choices that over time spiral, so that whether actions of his have been for good or ill they come home to roost. You can even question what actually happened in the boat with the other fugitives and the extent of his guilt, or rather, if his actions were violent and murderous of if the motivations were almost altruistic, aiming at rough justice at a point in history where all too often illegality pays more than honesty; case in point, the way in which detective Yumisaka cannot feed his family because he refuses to allow his wife to buy food off the black market.

The detective narrative bookends the film and Takakura as Aijmura just pings off the screen as he always does, and here as Inukai re-enters the story everything comes together thematically and the importance of the English title of the film comes to the fore. Inukai cannot escape his actions, his past, and Mikuni’s haunted visage dominates the end of the film as he seeks to explain himself, you suspect as much to himself as to the police.

For such a long film it’s hard to point towards anything that could be cut, because to have done so would have meant the creation of a totally different film. Taking out much of the middle part following Chizuru would have made A Fugitive from the Past a more cleanly narrative crime film, but would also have excluded much of the social commentary. As Jasper Sharp notes in his introduction to the film, there are characters who resemble prominent politicians of the time, giving emphasis to the points the film intends to make. Yet as with most great texts, missing these references though likely making for a less rich experience never detracts from the film in any way. The emotional universality of the film, the quality of the performances - these transcend anything more ephemeral.

As to whether A Fugitive from the Past is one of the truly great Japanese films, that is not something I for one will comment upon here. It’s also an unusual experience in some ways. I struggle to imagine a film like it though there are hints of Shohei Imamura’s, Vengeance is Mine (1979), as it functions equally well as both a character drama and a narrative crime film.

Any classic requires multiple viewings over time, and with this being only my first viewing I can only say that the ensemble is superb, with a narrative which delves more subtly into character and fate (and karma) than most detective narratives do.

Long-time anime dilettante and general lover of cinema. Obsessive re-watcher of 'stuff'. Has issues with dubs. Will go off on tangents about other things that no one else cares about but is sadly passionate about. (Also, parentheses come as standard.) Looks curiously like Jo Shishido, hamster cheeks and all.

posted by Richard Durrance on 06 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 05 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 02 Mar 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 25 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 12 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 10 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 07 Feb 2026

posted by Richard Durrance on 03 Feb 2026