Written by Majkol Robuschi on 04 Sep 2025

Distributor • Price

In what promises to be a deep dive into the golden age of the auteur JRPG, I recently began revisiting Bandai Namco’s Tales of saga, giving myself the chance to rediscover each of its many installments. Of course, as many will know, not all of the games in this series were officially localized by the Japanese publisher, and at the time of writing, Bandai Namco is busy with a brand relaunch to celebrate the franchise’s 30th anniversary. Even so, the only two titles currently remastered for today’s audiences are Tales of Graces F—already available on modern platforms—and Tales of Xillia, scheduled to release later this year across all contemporary consoles.

Some fans have expressed disappointment at Bandai Namco’s decision to revive such recent entries, especially when entire generations of older installments are still missing from the libraries of English-speaking players. Thankfully, thanks to the tireless work of the fan community, it’s now possible to experience nearly the entire series in English through translation patches, which localize most of the saga’s “mothership” titles—that is, the mainline Tales of releases. Naturally, my attention turned immediately to Tales of Phantasia, the very first entry in the series, and one of the most technologically ambitious games ever released for the Super Nintendo.

As many will be aware, Tales of Phantasia first arrived officially in Europe only in its Game Boy Advance version, a handheld port that was, however, notorious for its translation errors and limited technical capabilities, which undermined the experience of the PS1 edition it was based on.

For context, Tales of Phantasia was first released for the Super Famicom in 1995, and later ported to PlayStation in 1998. All subsequent ports, for Game Boy Advance and PlayStation Portable, were derived from this PlayStation version, which featured an expanded and refined combat system along with mechanics that would go on to become staples of the series.

Ideally, I would have preferred to experience the latest edition published by Bandai Namco in 2010, Tales of Phantasia Cross Edition, a version that extremely substantially expands the gameplay and enriches the narrative by adding a new character to the story; however, as I write, this edition of Tales of Phantasia, which is considered by Japanese fans to be the definitive one (albeit perceived as divisive due to the changes made to the narrative), has not yet been fan-translated. A real shame, considering that Bandai Namco does not seem interested in reviving the series' founding title through official channels.

My choice was therefore redirected toward the PlayStation edition, which features character sprites based on illustrator Kosuke Fujishima’s designs, translated by the fan group Absolute Zero in 2007. It wasn’t my first encounter with Tales of Phantasia, though, as I had already enjoyed it on SNES years earlier thanks to the legendary English fan translation by DeJap, a group famous in the early 2000s for localizing 16-bit classics such as Super Mario RPG, Bahamut Lagoon, and Dragon Quest VI.

At this point, I couldn’t resist delving into the game’s development history as an intriguing prelude. Unfortunately, reliable information available online is scarce and fragmented. What we do know is that Tales of Phantasia originated from an unpublished script written by Yoshiharu Gotanda, titled Tales Phantasia. Gotanda, a Japanese programmer, shopped his pitch to several publishers in hopes of securing support. Enix turned him down, but Namco—up until then focused mainly on arcade titles—expressed interest. Much of the original concept, however, was heavily altered, and the project spiraled to the point that Gotanda was ultimately removed from development. It was hardly a setback: soon after, he founded tri-Ace, the celebrated studio behind Valkyrie Profile and the Star Ocean franchise.

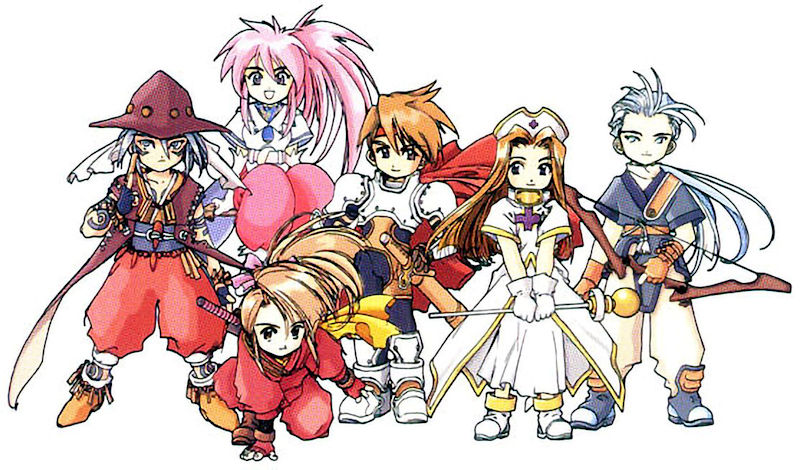

The drafts of the main characters from Tales Phantasia

From scattered sources, we learn that Gotanda’s original Tales Phantasia script was structured in three acts, following three separate groups of protagonists across different eras, all connected by their encounter with Dhaos, a mysterious sorcerer from a distant planet who opposed the spread of magical technology. Internal disputes led to large portions of this storyline being cut, leaving only the main beats intact while some of the second act’s material was relegated to side quests. In light of this, many narrative elements in Tales of Phantasia make far more sense once the troubled development is taken into account.

Narratively, Tales of Phantasia presents itself as a quintessential ‘90s RPG, embracing all the familiar tropes of the genre. The story follows swordsman Cless and healer Mint, descendants of the heroes who once defeated Dhaos. When the dark sorcerer is resurrected, the two must travel back in time to uncover a way to defeat him once and for all. Along the way, the party grows with new faces, and players traverse a world made increasingly familiar through extensive backtracking.

The focus, however, is less on the overarching plot and more on the dynamics between characters, which enrich the otherwise traditional cast. The PlayStation version introduces elements that would become series trademarks, such as “skits” (Face Chats), short dialogue scenes where characters discuss the current situation while expressive 2D portraits display their personalities in detail. These were absent from the SNES and GBA versions, but thanks to CD-ROM storage, they were added to the PS1 release alongside a strong Japanese voice cast.

As would become tradition for the series, Tales of Phantasia shines when its quirky protagonists take center stage. It’s hard not to be charmed by Arche’s cheeky and childlike nature, or Klarth’s (Klaus, in official translations) dry “dad humor.” The central plot soon reveals its time-travel twist, with Dhaos requiring defeat in the past, present, and future. This structure allows players to revisit familiar locations across different eras and introduces new characters like Chester, Cless’s childhood friend, and Suzu, a ninja added only in the PlayStation version. These arcs feel almost like separate seasons of an anime: one spanning past and present, the other set in the future. Of course, the narrative oscillates between highs and lows, sometimes leaning on convenient fantasy tropes and shallow political exposition.

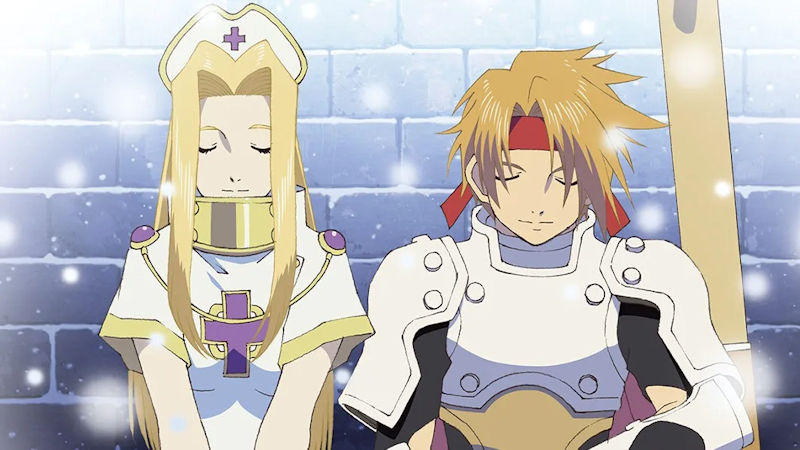

The Face Chat function adds so much personality to simple party interactions!

The inclusion of new characters in the group of heroes thus allows the cast to shine through new group dynamics, often recounted precisely in the amusing Face Chats viewable on the map, but also in many short sequences that are nonetheless rich in personality (and humour). In this sense, while the late inclusion of Suzu may at times seem superfluous (after all, she is a character added specifically in this version), it is the arrival of Chester that most enriches the tension among the protagonists.

Cless's childhood friend must suddenly confront a familiar face, but one clearly strengthened by the previous adventure and rendered immensely more capable in the art of combat. Always used to hunting with his friend, Chester immediately recognizes Cless's growth, and it is only through optional events that one can discover that while his companions sleep a well-deserved rest at the local inn, the archer trains hard in secret nightly sessions to reach their level of experience. Entirely optional events that also modify the relationship between him and the half-elf witch Arche, impressed by the boy's stoicism.

The theme of time travel, however, is not integrated into the narrative as one might expect and does not even seem to be considered central to the world-building system. While admitting that it remains extremely interesting to rediscover familiar places to see the differences between different eras, it is equally disappointing to note that the player has no agency in this matter, and that the game does not integrate enough elements to make the passage of time credible, such as NPCs present in the same places in different eras, or maps that are absolutely indistinguishable from those seen before. Which, for a video game published on the same platform that saw Chrono Trigger released just a few months prior, is without a shadow of a doubt a shame.

Another weakness lies in the villain himself. Dhaos is framed more like a deuteragonist than a true antagonist, yet most of his backstory is withheld until the very end. Players see characters speculate about his motives, but genuine insight or confrontation is absent until the final battle, when a few hurried lines reveal his tragic past. The sudden sci-fi twist could have been impactful, but here it feels undercooked. Small wonder, then, that Gotanda went on to create Star Ocean—under Enix, ironically enough.

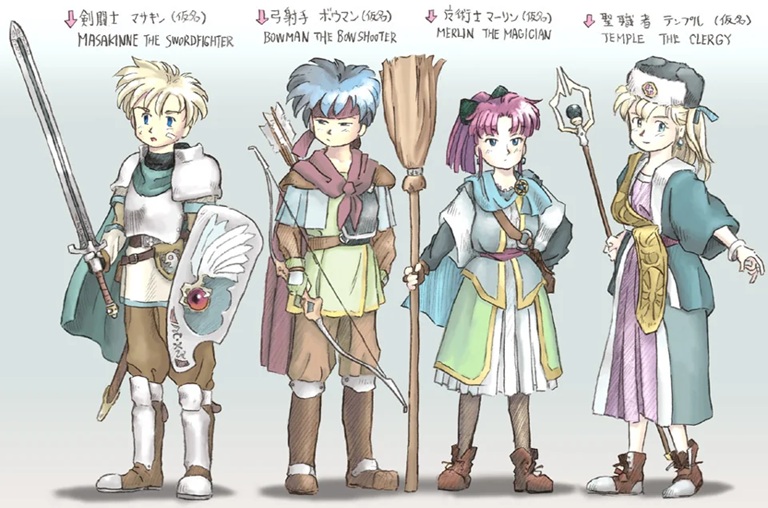

The 4 episodes OVA is a loose adaptation of the game's plot, with some differences. It's mostly an eye-candy for fans, but it adds more to the flimsy writing of Dhaos.

Even so, Tales of Phantasia delivers a memorable ending. The heroes come to realize they aren’t so different from the foe they’ve been fighting, complicating the binary of good and evil. While this doesn’t excuse Dhaos’s atrocities, it highlights the moral ambiguity at play. The story closes with hope, as order is restored and each character must return to their own time—a bittersweet farewell staged with all the naïveté of its era, but heartfelt nonetheless.

Context is essential to fully appreciate Tales of Phantasia. Namco’s deliberate omissions and the game’s troubled development are still obvious today. That said, supplemental media in Japan has fleshed out the story, such as Ryuji Matsuki’s light novel Tales of Phantasia: The Untold History, centered on Winona Pickford, a crossbow-wielding heroine originally intended as the lead of Gotanda’s first act. While non-canon, it ties into the original script. There’s also a four-episode OVA, Tales of Phantasia: The Animation, which takes plenty of liberties with the game’s story.

Mechanically, Tales of Phantasia is just as significant, pioneering the Linear Motion Battle System. This real-time, side-scrolling combat system allowed players to chain combos and cast spells in battle—an unprecedented innovation for 1995. One character is player-controlled while three allies are managed by customizable AI. Up to two human players can join in, though the camera makes larger-scale co-op impractical.

The PlayStation version updated the system, allowing directional attacks and assigning special skills to attack-button and d-pad combinations. However, movement remains semi-automated unless accessory slots are sacrificed, leaving players with the frustrating sense of not being fully in control—especially with Cless, the party’s only physical fighter for most of the adventure. Combined with frequent interruptions during spell animations, battles can become tedious despite their innovative core.

Battles are fun and engaging at first, but the novelty fades quickly once spells start to keep pausing the flow of combat.

As is tradition for JRPGs, the game includes many secrets and collectible elements, such as recipes, titles (purely accessory in this chapter) for customizing characters, secret equipment, and optional bosses. The final part of Cless and Mint's epic also allows travel across the world of Tales of Phantasia on the back of winged mounts, greatly reducing the navigation times that up until then forced the player into constant backtracking between continents. This is perhaps the moment I most appreciated the sense of freedom and discovery in Tales of Phantasia, which is so characteristic of '90s JRPGs: the total freedom to discover secret dungeons, follow hints hidden between the lines of an NPC's dialogue, or return on my steps to familiar places to find something new and unexpected waiting for me.

And indeed, while admitting the game's narrative limits and its structural flaws, I cannot help but look at Tales of Phantasia as a wholly respectable classic video game, one that can also be completed entirely in multiplayer should one wish. It is a first chapter that manages, in every way, to include all the characteristics that have made the franchise famous and appreciated to this day. In its simplicity, one can sense the beat of a naive heart that still reverberates with the sense of adventure and discovery of a video game genre that has, unfortunately, atrophied over time and become increasingly conformist to industry standards.

Majkol (aka Zaru) is an Italian queer writer (he/him – they/them) who has been immersed in the world of video game journalism for almost two decades. With a deep-seated love for anime and manga shaping his tastes and passion, he brings a blend of critical insight and heartfelt enthusiasm to his work, celebrating stories that challenge norms and embrace diversity. Find him on his blog, Also sprach zaru_thustra.

posted by Ross Locksley on 03 Sep 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 26 Aug 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 20 Aug 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 15 Aug 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 06 Aug 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 05 Aug 2025

posted by Majkol Robuschi on 25 Jul 2025

posted by Ross Locksley on 25 Jul 2025